“I don’t understand this obsession with upending what people have done before us”

Architect Manfreð Vilhjálmsson was the first recipient of an honorary award at the Icelandic Design Awards 2019. Here is an interview with Manfreð, taken by Marteinn Sindri Jónsson, due to that occasion and was published in the 10th edition of HA magazine.

“I consider myself extremely fortunate to have gone into architecture. I really found myself there. This is the kind of thing you can’t foresee: which path you end up going down.”

“My father was a carpenter, I was going to be a carpenter. But then I wandered off course, as one says.” Manfreð, who was born in 1928, went by sea to study at Chalmers University of Technology in Gothenburg in the spring of 1949. “I was such a country type that I had a suitcase that my father had made out of plywood. It says a lot about the times back then.” Manfreð sailed with future president Vigdís Finnbogadóttir, who describes the travellers this way: “We were a generation marked by two milestone events in Icelandic history: the 1,000-year anniversary of the Alþingi in 1930 and the establishment of an independent republic in 1944, and we were also baby boomers who seemed to dare to go out and learn what people abroad knew better than us.”

Forged his own path

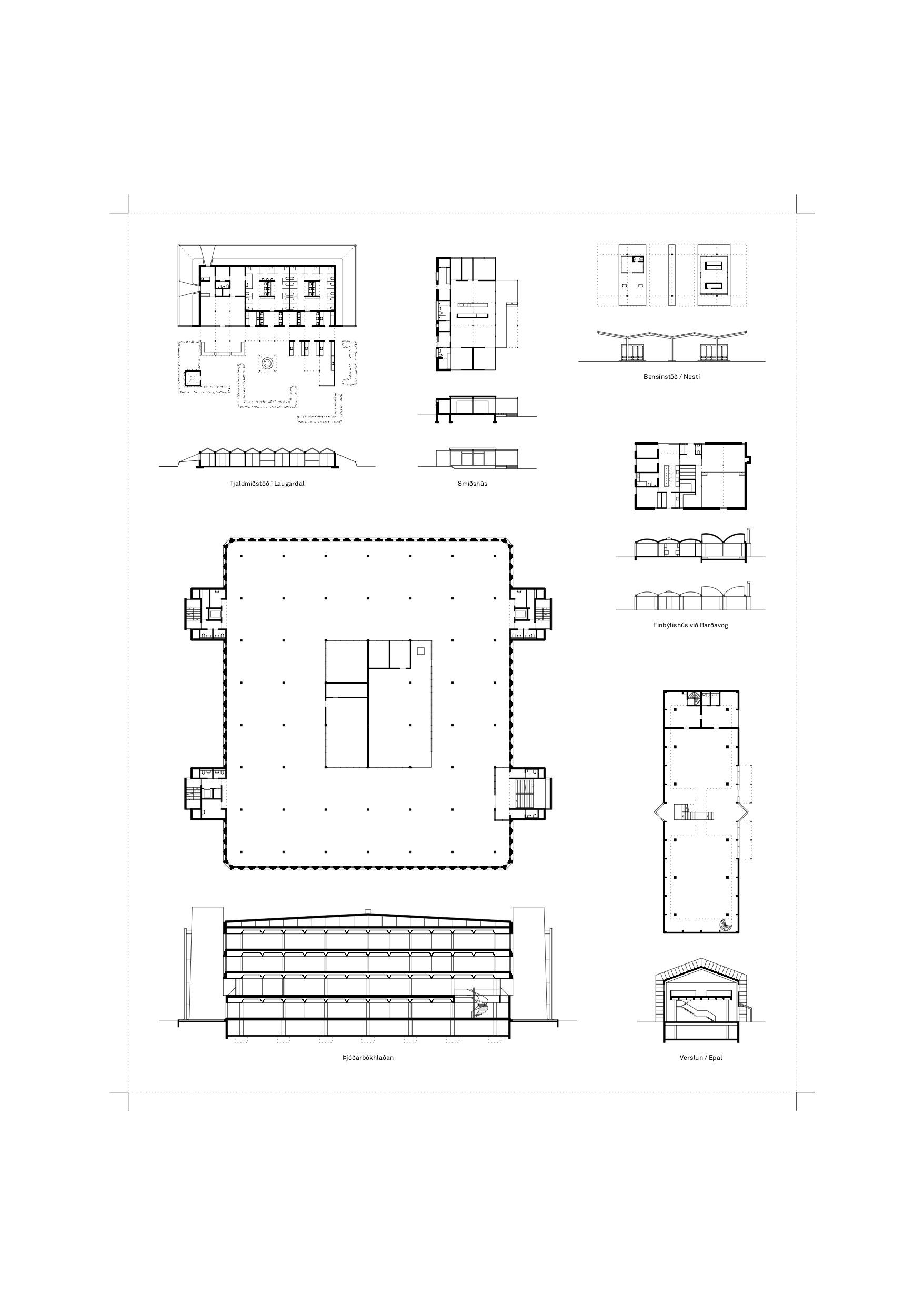

“I have tried to familiarise myself with the operation planned for a building in each case, and to get to know the owner. To integrate the building into the environment – I have tried to make that a focus. I think you can see it in various projects that I have worked on,” Manfreð says and names Sigurgeir Stefánsson’s bird museum in Ytri-Neslönd in the Mývatn countryside as an example in which he thought carefully about the interplay between the building and the environment. Manfreð started to forge his own path in Icelandic architecture early on, especially with respect to colour selection and the interplay between colours and building materials. His work is especially diverse, with everything from housing construction and planning in Fossvogur and Skálholt to avant-garde drive-in gas stations that made their mark on Reykjavík and Akureyri, public buildings such as Iceland’s national library and the Árbær church, and various apartment buildings and furniture and design objects, to name just a few.

Many important aspects of Manfreð’s art can be distinguished in his home in Álftanes. His use of colour and materials is carefully thought-out and Japanese influences characterise the modest interior where light partitions and sliding doors divide living rooms. “The windows face south – here out to the field, and here out to sea to the south. The north side is completely closed and almost windowless. I have always thought of the house like a horse out in the field that turns its rear end to the wind. Like the horses that you see grazing in front of us here.” This perhaps crystallises a certain perspective of Manfreð's that Halldóra Arnardóttir has described in the words of Þorsteinn Gylfason: “to think in Icelandic,” which involves “adapting ideas that [Manfreð] learned abroad to Icelandic conditions and culture.” Indeed, Manfreð has no doubt about how important it is for Icelandic architects to study abroad. He believes it is essential in a sparsely populated country like Iceland that those who practise architecture go abroad to broaden their perspective.

Found objects

When the conversation turns to modern architecture, Manfreð expresses doubts about the value of tearing down older buildings to make room for new ones. “I don’t understand this obsession with upending what people have done before us.” He references Halldór Laxness, who said that you can tell how cultured a nation is based on the state of its architecture, and says that although people have mixed opinions about existing buildings, he believes architects could pause a moment and respect the work of past generations.

Such thinking about utility can clearly be seen in Manfreð’s smallest works, which decorate his home. “I think one should use things, find another place for things,” he says about the bathroom cabinets, artfully made from old broomsticks. “I was in love with all broomsticks,” he says with a serious face. There’s no doubt about that, as the coat rack in the foyer is made of the same material. There is also a precious circular stool made from a welded iron rack with a thick, red plastic buoy for a seat – the so-called Tónabær stool. “This nonsense of mine is thanks to my good friend Dieter Roth. He would say that one should try to find a use for mass-produced things other than the intended one. And here is an example: this is just a buoy used by fishermen.”

“Of course one is a product of one’s time,” Manfreð readily admits, but many aspects of his work testify to his visionary thinking and one thing has hardly changed: “It’s like any other job, if you’re going to be successful, then you have to really work at it for years. It’s become a bit of an obsession, to look at what others have done and then try to make something decent out of it.”

Vigdís Finnbogadóttir and Halldóra Arnardóttir are quoted from the book Manfreð Vilhjálmsson arkitekt, which contains a detailed account of his work.