Icelandic Visual Heritage

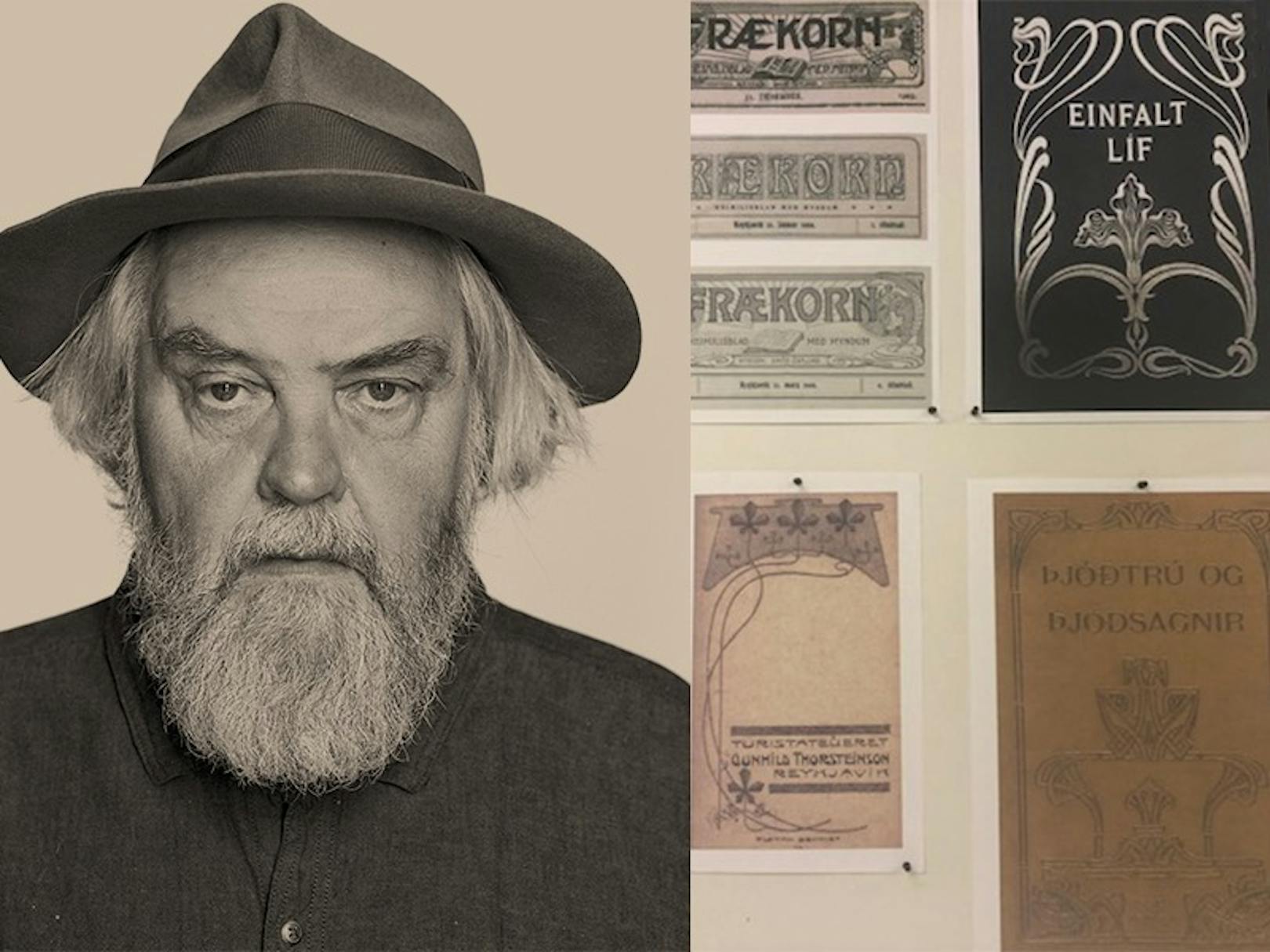

Icelandic Visual Heritage is the title of Guðmundur Oddur Magnússon’s ongoing research project on the history of applied graphic arts and graphic design in Iceland, which he carries out in collaboration with the Museum of Design and Applied Art, the University Library and Iceland University of the Arts. The first part of the research revolves around the history of forerunners and trailblazers. Shortly after the publication of Guðbrandur’s Bible in the 16th century, imagery and text became separated and didn’t meet again until late in the 19th century. In his research, Guðmundur Oddur traces the start of this reunion of imagery and text and follows the generation that formed the Association of Icelandic Graphic Designers, thereby laying the foundation for what is now known as graphic design in Iceland.

History has eyes in the back of its head – it is a rear-view mirror. Obviously, writing the history of a profession that has not been covered from a localised viewpoint raises many questions. The profession in question is called graphic design; the viewpoint is Iceland. The term alone, “graphic design”, raises questions. Although the profession itself has existed in some form for more than a century, the term itself didn’t become commonly known until around thirty years ago. Before that time, it was called “advertising design”, before that “drawing” or “practical drawing”, and before that, so-called artists were hired to do the job.

It is also a fact that some people are more in tune with their present and past than others. They care when things are looking bleak. Also, at times, social, religious or technical changes happen, causing revolutions in form or transformations. The history discussed here began with the second industrial revolution during the latter half of the 19th century. One of the consequences of this revolution was the demolition of a sense of beauty, as trained craftsmen were displaced. It is often pointed out that before this time, the different fields of visual arts education were not separated, although sometimes art was divided into visual and applied art. Art and practicality had lived together happily for a long time; the idea and the execution came more or less from the same individual. Then industrialisation and the laws of the market came between them, causing more division of labour, as special job titles came into being.

When examined closely, we see that all man-made products, large and small, are children of their time. No one is as original as they believe themselves to be. We are all born into a particular zeitgeist, in a place that is not of our choosing. When we look back, those practitioners who stand out were typical rather than original. Thus, ideology is created, and, with it, the history of art and design. All large movements in art and design, seen in the rear-view mirror, are born in a certain place or even places, spread like an infection, at various speeds, and take on localised images based on know-how and materials.

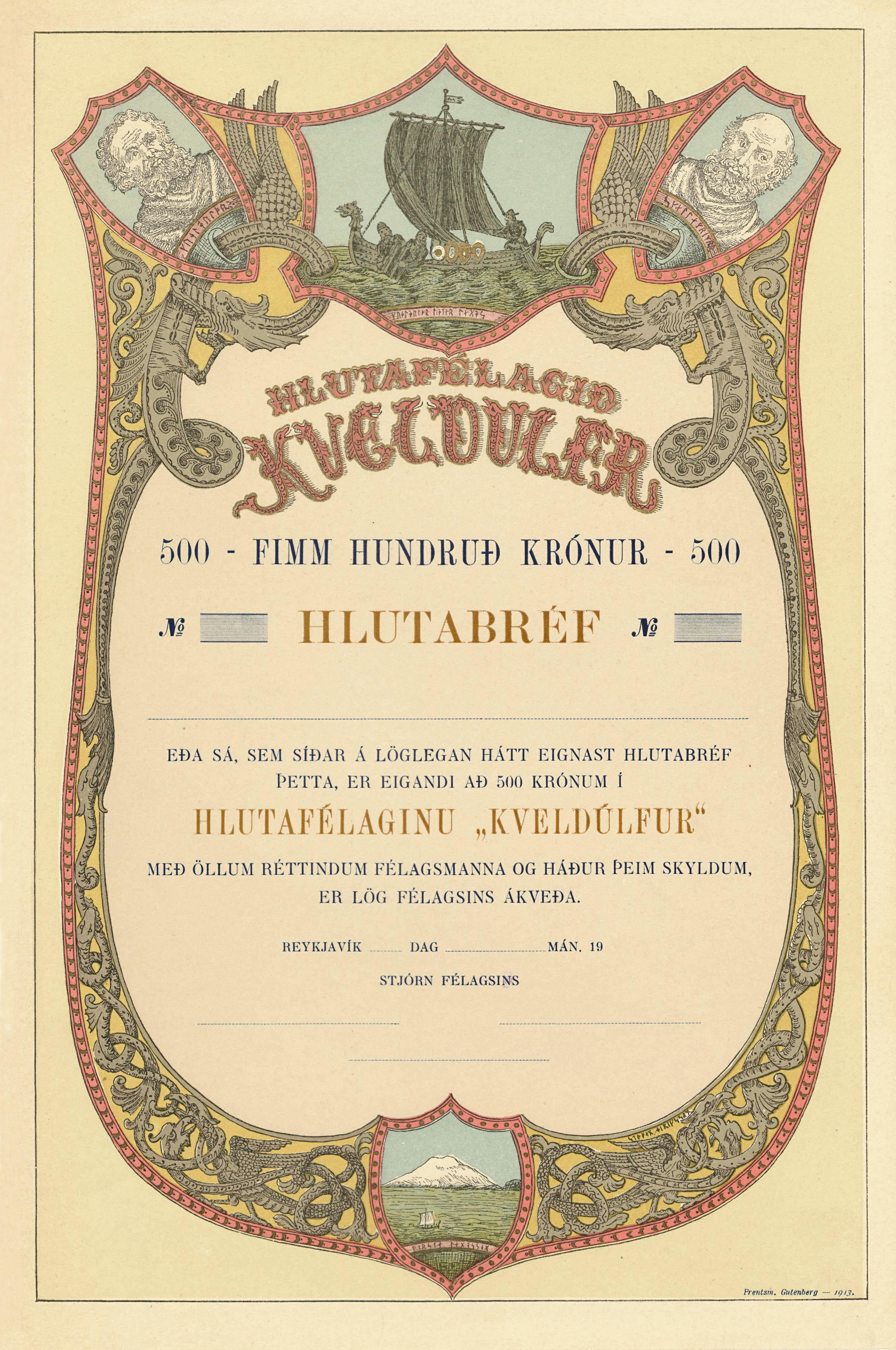

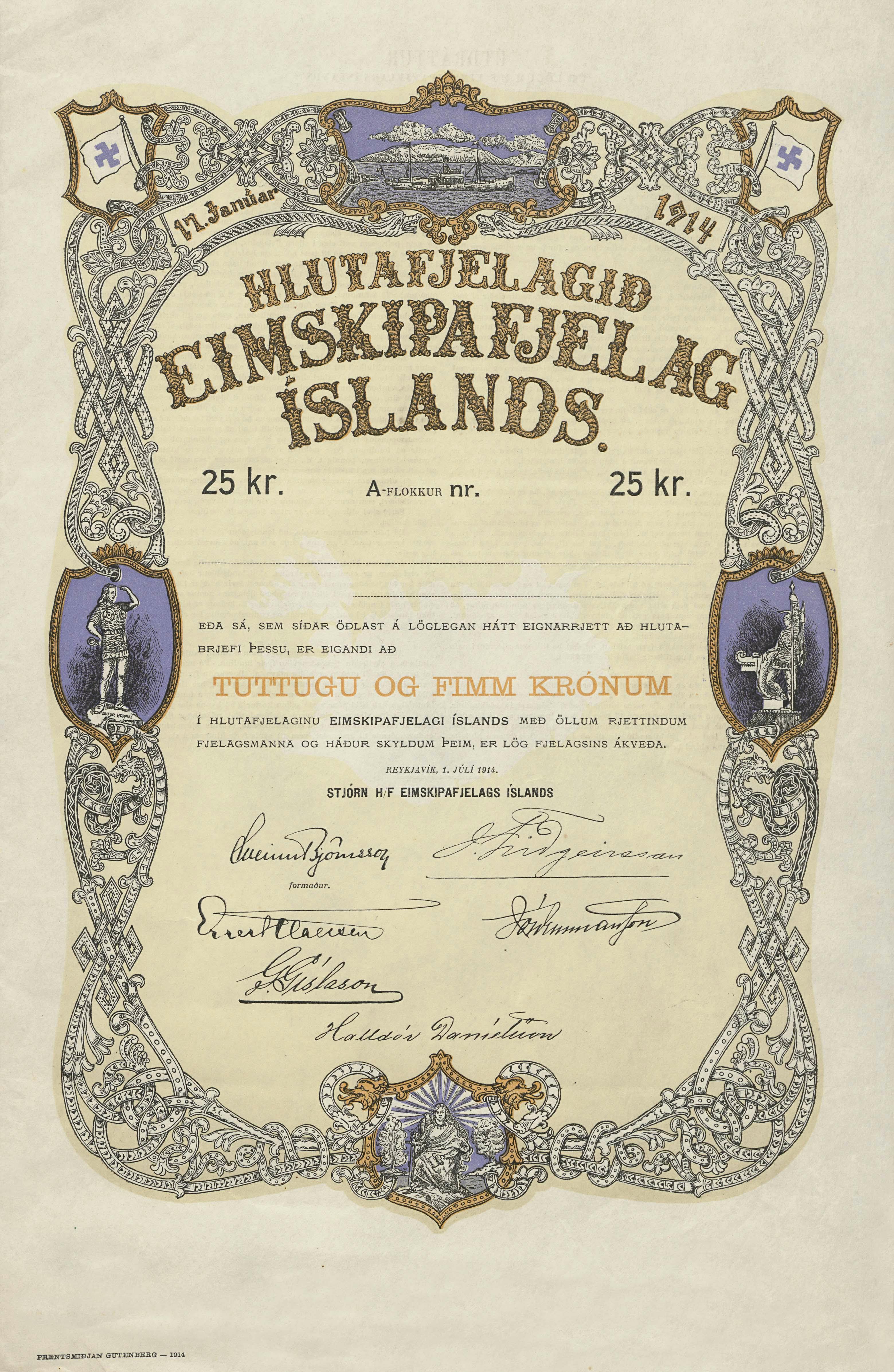

Now, after a few years of mapping it out, we know that neoclassicism came to Iceland via people such as the printer Sigmundur Guðmundsson, the painter Sigurður Guðmundsson and Benedikt Gröndal, the illustrator and poet. We know that Art Nouveau came here through a Swedish missionary and printer, David Östlund, and that the Jugend-style came through the printer Oddur Björnsson. These movements were to a large extent a resistance against all the crap that mechanisation had brought and the accompanying dissolution of beauty and aesthetics.

It can be said that the British Art and Crafts movement started certain trends in design history, such as Art Nouveau and Jugend. It’s main instigator, William Morris, was tightly connected to Iceland; he translated the old sagas along with Eiríkur Magnússon, whom he met in 1868. Morris was known for not accepting the break that had occurred between production and artistic aesthetics.

It is not always clear how ideas are carried from one person to the next or how they create a ripple effect. To my knowledge, no one has claimed that Morris had a direct influence on the creation and development of Icelandic visual arts. At the time when he visited Iceland, they can hardly be said to have been flourishing. Handicrafts did indeed exist, but not at as high a level as the ancient literature that had been preserved here. Upon taking a closer look, we discover that the carriers were actually two sisters.

Today, many people know of Sænautasel on the moor above Vopnafjörður and Jökuldalur in East Iceland. Sænautasel is the only remaining farm on the moor, as of the 19th century. Both Halldór Laxness and Gunnar Gunnarsson sought inspiration there and wrote novels about life on the moor. At the start of 1890, one of the farmers on the moor shot a reindeer outside the hunting season. News of this unlawful killing reached the gamekeeper who was the priest at Valþjófsstaður. The farmer’s son, who was set to take over the farm, became afraid and worried that the magistrate would imprison his father. The son wasn’t much of a farmer but was quite skilled at carpentry and at using his handiwork skills to carve decorations. He spent a long time that spring making a small chest decorated with intricate carvings of reindeer horns.

When summer arrives, he walks down the mountain to Valþjófsstaður and offers the chest as a present to the priest’s wife, in the hope of placating the couple so that they won’t press charges against his father. They receive him warmly – amazingly so. The lady invites him to stay with them for the summer and study Danish. Later that summer, she holds a raffle in Vopnafjörður to collect money for the farmer’s son to study woodcarving in Copenhagen.

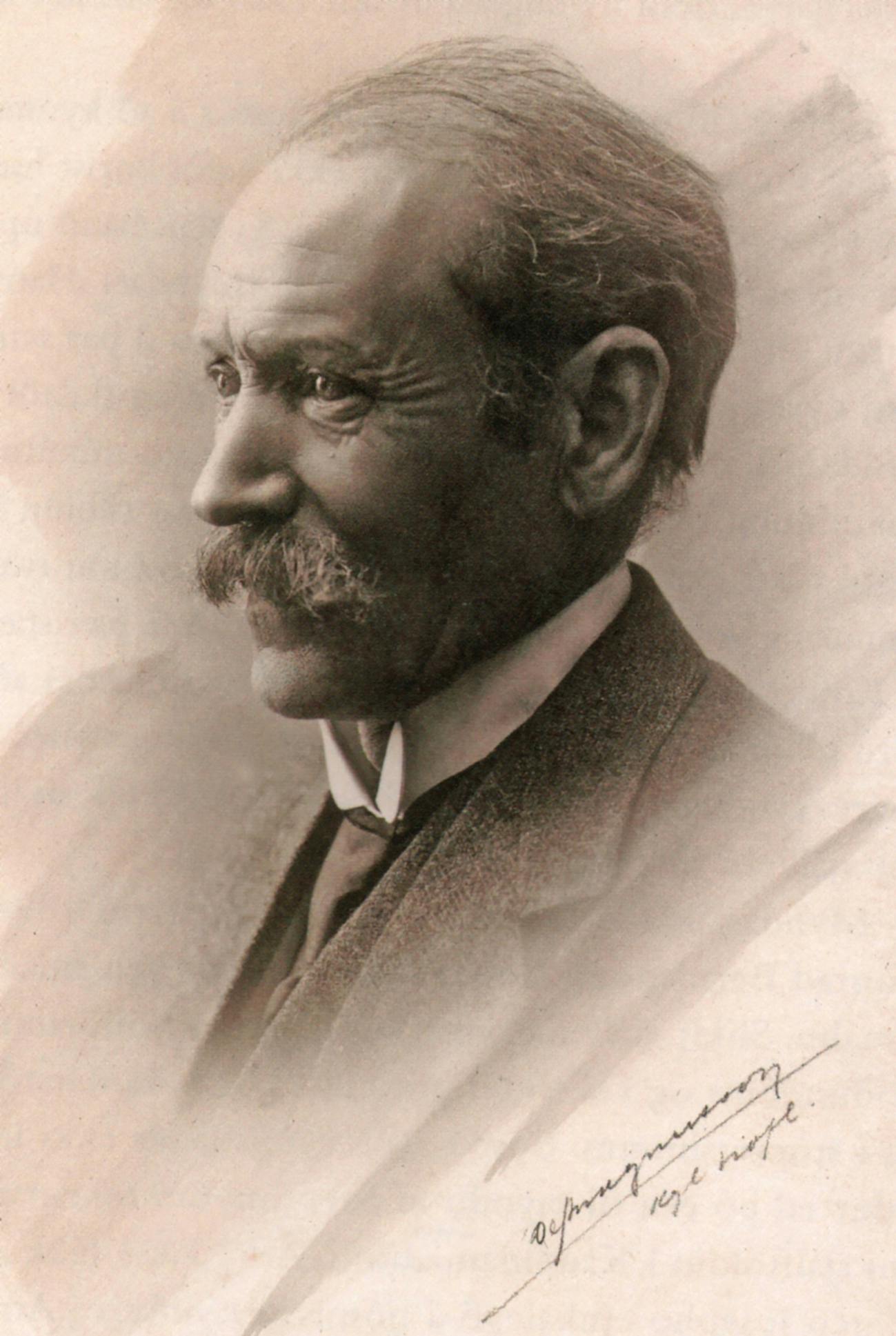

This skilled son of the moor was called Stefán Eiríksson and he sailed to Copenhagen from Djúpivogur in the autumn of 1890, at the age of 27. His contemporary in Copenhagen, Guðmundur Hannesson (later a doctor in Akureyri who advocated Oddur Björnsson’s foundation of a printing press in 1903), describes Stefán’s arrival in Copenhagen thus: “an Icelandic boy joined our group who soon caught the attention of everyone who met him. He didn’t cut an imposing figure, nor was he schooled in any way, other than the old school of a decent upbringing in the Icelandic countryside.” Guðmundur says Stefán was poor and forlorn and had arrived solely to learn woodcarving, which nobody was studying at the time. It was not considered art to be able to carve a little bit. He had no grand sponsors. However, this boy caused more of a stir than most of the other students and was very popular with Danes and Icelanders alike.

It is not completely true that Stefán had “no grand sponsors”. Unbeknown to Guðmundur Hannesson, the wife of the priest at Valþjófsstaður who had organised Stefán’s studies in Copenhagen was Soffía Emilía Einarsdóttir, from Brekkubær in Reykjavík, who was both well educated and artistic. Before her marriage, she had lived in Cambridge, England, for seven years, with her sister Sigríður Einarsdóttir, the wife of Eiríkur Magnússon. William Morris was an established friend of the family and they visited each other often.

Stefán spent seven years in Copenhagen and returned home in 1897. In Gunnar Gunnarsson’s book “Heiðarharmur”, there is a fantastic story about Stefán, who is called Little Nonni in the book. In the story, the women praise his work, but the men think he is a good-for-nothing who has ruined his father’s life’s work. His future mother-in-law enthusiastically claims: “You sing the Lord’s praise with your work – that much is true. You must not forget, Nonni, that it is the Lord who has blessed your hands with this artistic gift, so you may worship him among people who turn their back on the most glorious gifts of nature.”

Stefán moved to Reykjavík with his teenage sweetheart and opened a school for drawing in around 1900. Among his students were many of the first generation of Icelandic visual artists, including Guðjón Samúelsson, Guðmundur from Miðdalur, photographer Sigríður Zoëga, Ríkarður Jónsson and Gunnlaugur Blöndal.